Moxie: Alex Honnold & The Voice On The Wall

Mar 24, 2025

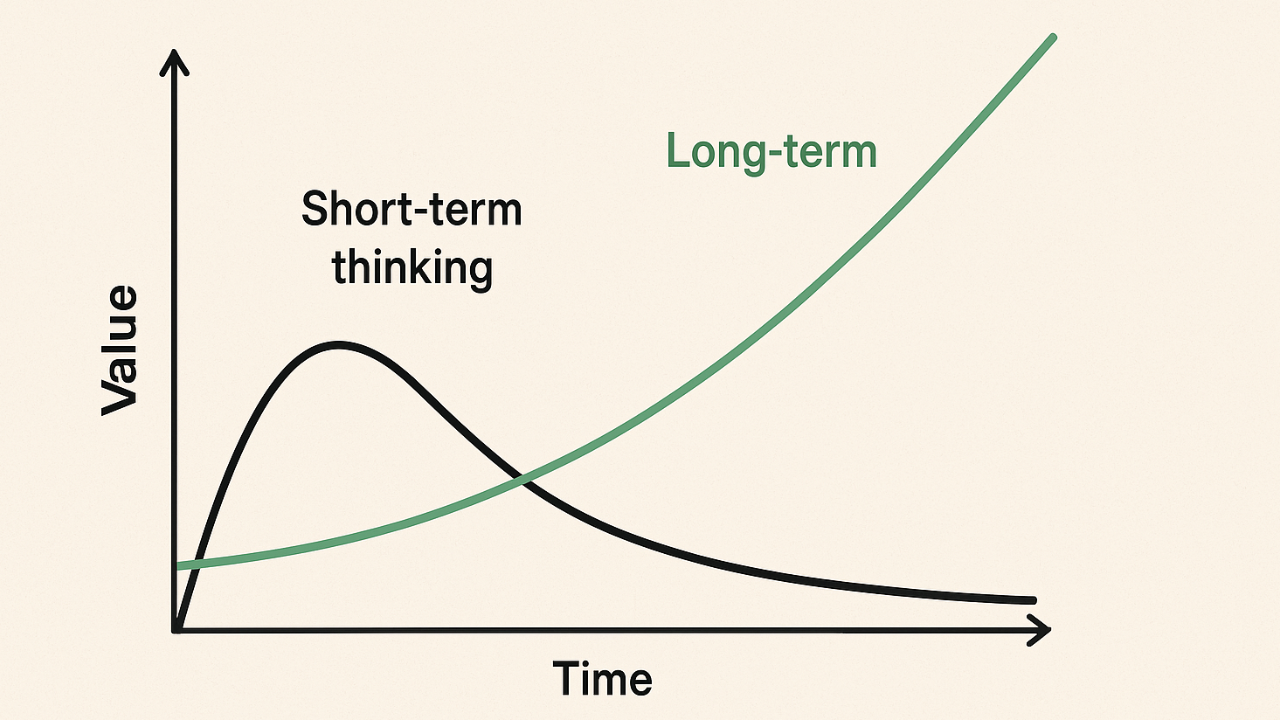

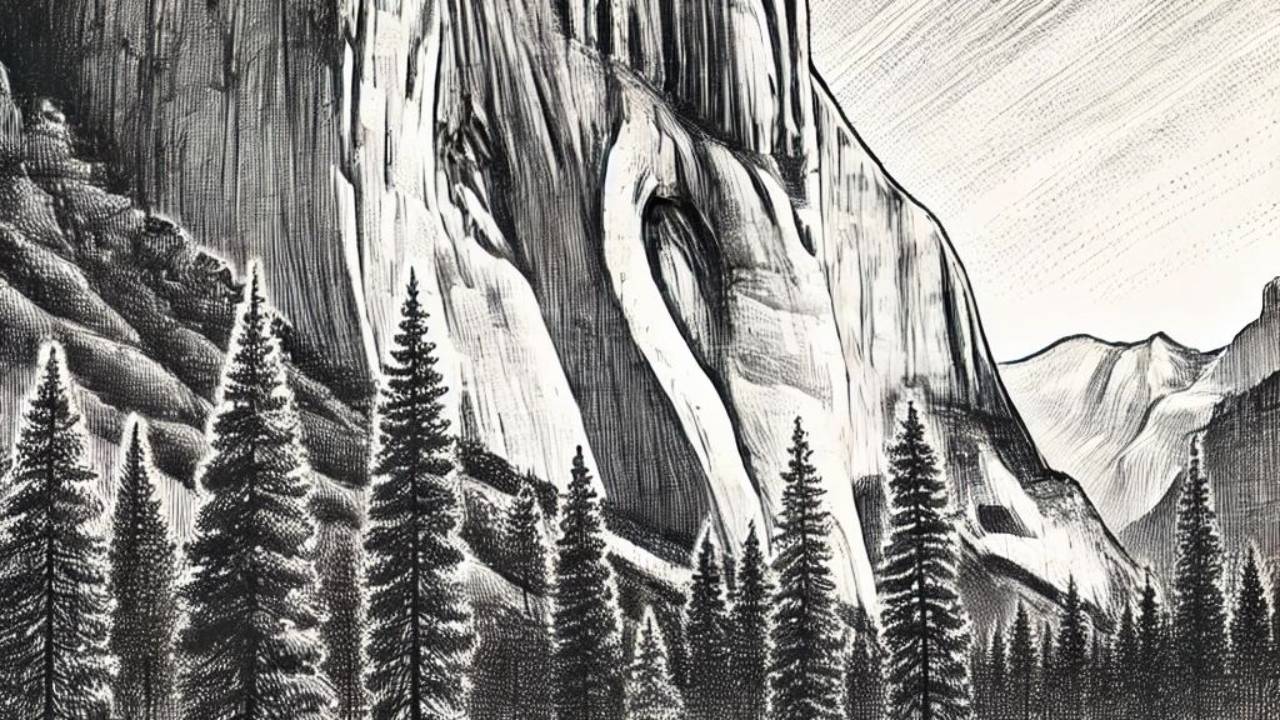

One StoryClimber Tommy Caldwell called it, "The moon landing of climbing." The New York Times described it as, "One of the greatest athletic feats of any kind, ever." Maybe you've seen the documentary. Maybe you haven't. No matter, it's all worth a second look. On June 3, 2017, Alex Honnold did the impossible when he climbed the iconic 3,000-foot granite wall of El Capitan in Yosemite National Park—without a rope. Just Alex. And the voice in his head. At first glance, it seems inhuman: 3,000 feet without a rope? No backup? No margin for error? Wasn't he afraid? At all? It turns out, behind Alex's extraordinary achievement, there was a method. What most of us view as a threat, Alex trained himself to see as a challenge. How? He spent nearly a decade preparing. He first climbed El Capitan with ropes in 2008, and spent the next nine years returning to it over and over again. He focused on a route called Freerider, which includes roughly 30 pitches (climbing segments), some rated among the most difficult in the world. He broke the wall into sections and rehearsed each one with gear—hundreds of times—until he could climb them fluidly, without thought. He kept meticulous notes on handholds, footholds, body positions, even weather conditions. In some places, he memorized entire pitch sequences down to the number of steps and breaths. He spent months working through just one section—the Boulder Problem—a pitch with a thumb-press move so precise, he described it as "a karate kick with total commitment." For years, he studied the wall. He memorized every sequence. He rehearsed every step—until his body could move without hesitation. Alex didn't eliminate his fear. He became intimate with it, until it simply stopped being an obstacle. Truth be told, Alex's feat was more psychological than it was physical. The mastery Alex demonstrated transcended physical prowess, yes. But, scientists who later scanned Honnold's brain wanted to understand how he could remain so calm in situations that would terrify most humans. The result? His amygdala—the brain's fear center—barely activated, even when shown disturbing or high-stress images. Is he wired differently than the rest of us? Maybe. But fear isn't just biological. On the wall, Alex had a voice—not yelling, not panicking—but steady. Clear. Focused. Deliberate. "If I start thinking emotionally, it's over. I repeat the plan. I talk myself through the sequence." That voice wasn't born overnight. It was built. What you and I interpret as threat, Honnold spent years reframing as familiar. What most people fear, he studied. Rehearsed. Made his own. He didn't suppress fear. He reframed it. He rewired his brain—through repetition, language, and belief. Climbers have a word for tough routes. They call them problems. And that's exactly how Alex treated the wall: Not a danger to avoid. A problem to solve. Two Quotes“Fear is always there. But if you let it consume you, you’ll make mistakes.” “We suffer more in imagination than in reality.” Three Takeaways

One More ThingYou don’t have to climb El Capitan to train your voice. You just have to notice it. Your inner voice is always there. If you teach it how. |